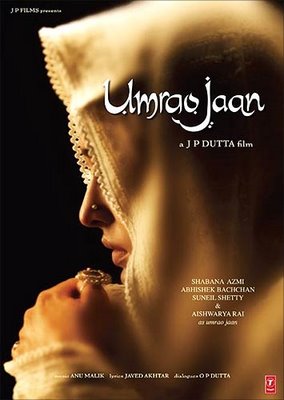

Strapline: In a multicultural world, it's time to think beyond the veil

RECENTLY, British MP Jack Straw urged Muslim women to discard their veils. He argued that wearing the niqab — the piece of cloth that some Muslim women wear to cover the face, hiding everything below the eyes — is a "visible statement of separation and difference", and that wearing the veil could harm community relations.

The argument is specious, as demonstrated by Mr Ziauddin Sardar, a columnist for the New Statesman. On Oct 16, he wrote: "How separate and different are women coming to consult their MP — presumably to secure or defend their civic rights as British citizens — seeking to be?"

Still, Mr Straw had his supporters. Veils "suck", said novelist Salman Rushdie. Even Prime Minister Tony Blair joined the chorus, calling the veil a "mark of separation".

This controversy is not new. There have been public disputes in France, Turkey and elsewhere about Muslim headscarves. I don't think the veil issue in Britain will evoke the same passions — among some mullahs and their followers — as the Danish cartoons and the recent, anti-Islamic remarks quoted by the Pope.

Most commentators agree that Islam does not have a monopoly on the veil (it pre-dates Islam by centuries). The Quran asks for modest attire only, and does not order women to cover their faces or their bodies from head to toe.

Because some ambiguity surrounds the question of the veil in Islam, it can stand for various things. For some, it is a sign of oppression and male dominance; for others, it is a sign of religious piety.

For some, the veil even stands for Islamic feminism. "The veil is freedom. The veil is liberation. The veil is choice," chanted British protesters on Oct 14 in Blackburn, greeting Mr Straw in his constituency.

In a post-911 world of increasing discrimination, a number of Muslim women stopped wearing their headscarves in public. Paradoxically, a backlash was triggered among younger women, who began to assert their Muslim identity by wearing headscarves and veils. It is a mark of separation that they chose for themselves.

British women who wear the niqab, Mr Sardar noted, felt they could fully participate "in society without being demeaned, reduced and pigeonholed by the conventions of a commoditised consumer culture and its insistent sexualisation of women".

For now, the debate on the veil in Britain has crystallised around Ms Aishah Azmi, a teaching assistant who was suspended for refusing to remove her full-face veil during class, in the presence of male teachers. Last week, an employment tribunal dismissed her claim of discrimination.

Another, quite different, incident comes to mind. Not long ago, Indian tennis pro Sania Mirza, a teen Muslim icon, was chastised by hardcore Muslims in India for her short skirts and modern dresses. She valiantly stuck to her sartorial style.

Elsewhere, especially in the United States, feminists like Irshad Manji, Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Asra Nomani are challenging male hegemony in Muslim communities.

While Ms Manji, the author of The Trouble with Islam Today, strives for equal treatment of women in Islam, Ms Ali champions an overhaul of Quranic teachings to bring them more in tune to the present realities.

In her autobiography, My Life, My Freedom, Ms Ali, a former Dutch MP who now lives in the US, even suggests changing the doctrine of "virginity before marriage" in Islam. "If we manage to change that, women will be free," she once said in an interview.

Ms Nomani is another champion of her gender. In November 2003, she became the first woman in her mosque in West Virginia to fight for her right to pray in the male-only main hall, defying centuries-old gender barriers in Islamic tradition. In March last year, she organised the first modern, public woman-led prayer of a mixed-gender congregation.

Despite widespread, adverse Muslim reaction, it is women like Ms Manji and Ms Nomani who are redefining Islam in multicultural societies, and pressing ahead with their own fights.

Thankfully, for every Aishah Azmi, there is a Sania Mirza in the Muslim community. Someone once said that every intelligent person invents his own religion. This applies to both the Azmis and the Mirzas of the world. A truly multicultural and free society should allow them to follow their choice of religion and tradition — of course, within the boundaries of accepted social behaviour.

In the British context, going beyond the veil is the real challenge for politicians like Messrs Straw and Blair, who are struggling to cope with the radicalisation of a segment of Muslim youth angered at the deployment of British troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Full text also available here.